For 13 months, adding an alternate login email required an engineering deployment. A support ticket would come in, an engineer would add the email to a hardcoded list in our codebase, open a PR, get a review, merge, and deploy. Average turnaround: eight days. Slowest: nearly a month.

The problem wasn’t just slow—we were storing PII directly in our repository. Operations couldn’t search for user emails. And we were burning engineering time on what should be a self-service operation.

We recently shipped a solution that changed everything: 15-second average turnaround, zero support tickets, 100% elimination of code deployments for this workflow. Here’s how we built it—including what didn’t work.

The Problem: PII in Code and Multi-Day Turnaround

Our users often need to add alternate email addresses for logging into Tint’s Protection Portal. Maybe they didn’t have or want to access their primary email with their organization, or they just wanted a backup login method. Reasonable request.

But our implementation made it painful. We maintained a hardcoded list of alternate emails directly in our codebase. Why? Well, as a startup, sometimes we have to move fast. And sometimes that means we have to follow the KISS principle, implementing the most simple solution and refactoring later when needed.

Unfortunately though, this simple approach meant that when a user needed to add an alternate email, they had to contact support.

Yikes.

Support would then create a ticket and an engineer would have to follow the entire software development lifecycle process:

analyze ticket -> open pull request -> get review -> merge -> deploy to prod

The numbers tell the story:

- Average turnaround time: 7.98 days

- Fastest resolution: 3 hours

- Slowest resolution: 28.53 days

- Support ticket volume: ~2.46 tickets per month (33 tickets over 13 months)

- Total manual additions: 70+ emails across 34 PRs

- Average emails per ticket: 2.15

But the operational pain was only part of the problem. We were storing PII in our codebase (security risk), alternate emails weren’t visible to operations (impossible to troubleshoot), and the entire process required engineering time for what should be self-service.

We needed to fix this.

What We Tried First: The B2C API Detour

When we started investigating solutions, Stytch (our authentication provider) seemed like the obvious choice. They handle email verification via magic links, which we already use for login. Perfect, right?

We started implementing with Stytch’s B2C API, which allows users to have multiple emails. We were halfway through the implementation, writing tests, feeling good about our progress. Then we tried it in our local development environment once enough progress had been made to test it.

It didn’t work.

Turns out, we use Stytch’s B2B product, not B2C. And B2B has a critical limitation: each member can only have one email address. We’d spent several hours building something that fundamentally couldn’t work with our setup.

Admittedly, we heavily use AI to assist with development of features here at Tint. Unfortunately, search engines and LLMs seem to bias towards Stytch’s B2C documentation, since it’s probably their most popular product. In hindsight, we should have manually cross-checked with Stytch’s B2B documentation to ensure the same features were available.

We reached out to Stytch’s official #stytch-questions on Slack hoping there was a workaround we’d missed. Their team confirmed: multiple emails per member isn’t supported in B2B, and while they’d consider it for their roadmap, it wouldn’t be implemented anytime soon.

We had to pivot.

The Solution: One Member Per Email (Yes, Really)

If Stytch’s B2B API only allows one email per member, we’d work with that constraint: create a separate Stytch member for each alternate email.

It sounds counterintuitive—and honestly, it felt weird at first—but it solves several problems:

- Each email gets its own Stytch member with proper verification

- We can use Stytch’s standard verification flow without workarounds

- Each email is independently verifiable and deletable.

To maintain the relationship between Tint’s user concept (one user, many emails) and Stytch’s member concept (one member, one email), we needed a mapping layer. We chose DynamoDB to store these mappings, which we’ll explain in detail later.

The final system has four key components:

- PostgreSQL tables for storing user records and another for alternate emails

- Stytch integration for email verification via magic links

- Self-service UI in the Protection Portal (built with Next.js) for email management

- Internal authentication service (built with Remix) to orchestrate verification and handle Stytch operations

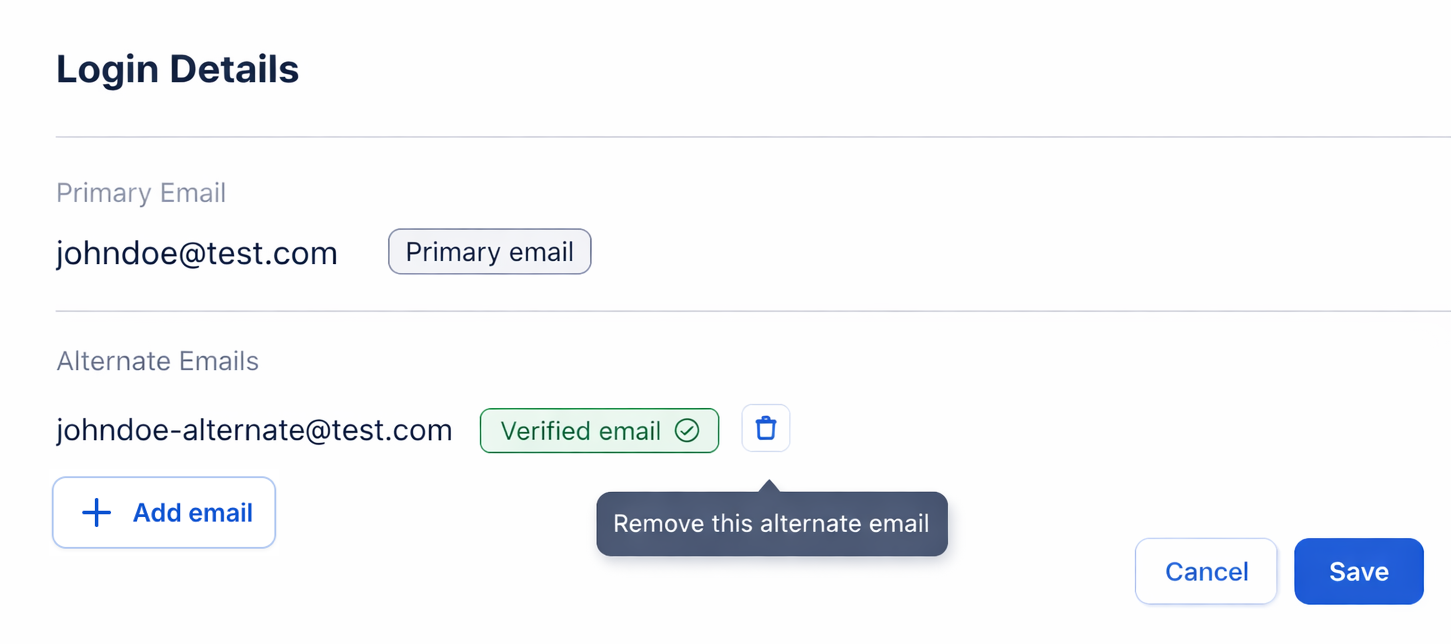

The Self-Service Interface

Users manage their alternate emails through a clean, intuitive interface in the Protection Portal. The UI shows all their verified emails, pending verifications, and provides clear actions for adding or removing emails.

In edit mode, users have full control over their login credentials:

- Add new alternate emails - Add up to 5 alternate emails with instant validation

- Delete verified emails - Remove any verified alternate email with a single click

- Resend verification links - Request a new magic link for unverified emails if the original expired or wasn’t received

The Save button commits all changes, while Cancel discards pending actions and exits edit mode.

This gives users complete visibility and control over their login credentials without needing to contact support.

Let’s dive into how we built each piece.

Architecture: How the Components Work Together

The Protection Portal is where our end-users manage their insurance coverage and profile settings. It’s built on Next.js with server actions, leveraging React Server Components for data fetching and Server Actions for mutations. This keeps sensitive operations server-side while providing a snappy user experience.

Our authentication service, built with Remix, handles all authentication flows and Stytch integration. This separation keeps auth logic centralized and maintainable.

Here’s how the components interact:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ End User │

└───────────────────────────┬─────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌───────▼────────┐

│ Protection │

│ Portal │

│ (Next.js) │

└───┬────────┬───┘

│ │

┌───────────▼──┐ ┌──▼──────────────┐

│ PostgreSQL │ │ Authentication │

│ │ │ Service │

│ - User │ │ (Remix) │

│ records │ └──┬──────────┬───┘

│ - Alternate │ │ │

│ emails │ │ │

└──────────────┘ ┌──▼─────┐ ┌──▼───────┐

│ Stytch │ │ DynamoDB │

│ │ │ │

│ Magic │ │ User │

│ Links │ │ Mappings │

└────────┘ └──────────┘

Key architectural decisions:

- Next.js Server Actions for mutations: Email management operations happen server-side with proper authorization

- Remix for authentication: Centralizes all auth flows and Stytch integration

- Database as source of truth: Even if external services fail, our database operations succeed

- Cryptographically signed tokens: Verification callbacks use signed tokens to prevent tampering

- Soft deletes: Maintain audit trails by setting

deleted_atinstead of hard deletes - Atomic operations: Verification and deletion are idempotent with proper locking

- Multi-tenant design: All operations are scoped to organization to prevent cross-org data leakage

Why Cryptographic Signatures?

When a user clicks the magic link in their email, they’re redirected through multiple services before landing back in the Protection Portal. We use cryptographic signatures to ensure the verification data hasn’t been tampered with during this journey.

The authentication service generates a signed token after validating the magic link with Stytch. The Protection Portal validates this signature using a shared secret key. If the signature is invalid or the token has been modified, we reject the verification. This prevents attackers from forging verification callbacks or hijacking other users’ email addresses.

Database Schema: Designing for Case-Insensitive Lookups and Audit Trails

We created a user_alternate_emails table with careful attention to performance and data integrity:

CREATE TABLE public.user_alternate_emails (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT uuid_generate_v7(),

user_external_id TEXT NOT NULL,

organization_id UUID NOT NULL REFERENCES organizations(id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

email VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

email_lowercase VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

external_email_id TEXT, -- Stytch member ID after verification

created_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT NOW(),

updated_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT NOW(),

verified_at TIMESTAMPTZ,

deleted_at TIMESTAMPTZ,

);

To enforce further constraints at the database level, we added the following checks:

CREATE TABLE public.user_alternate_emails (

...

-- Ensure email_lowercase is always lowercase

CONSTRAINT email_lowercase_check CHECK (email_lowercase = LOWER(email)),

-- Enforce max length

CONSTRAINT email_max_length CHECK (LENGTH(email) <= 255),

CONSTRAINT email_lowercase_max_length CHECK (LENGTH(email_lowercase) <= 255)

);

We also created indexes to improve performance:

-- Index for fast case-insensitive lookups

CREATE INDEX idx_user_alternate_emails_org_email_lowercase

ON user_alternate_emails(organization_id, email_lowercase);

-- Partial unique index: only one verified email per org

-- Allows multiple unverified emails during verification process

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX idx_user_alternate_emails_org_email_verified

ON user_alternate_emails(organization_id, email_lowercase)

WHERE verified_at IS NOT NULL AND deleted_at IS NULL;

Why We Chose This Design

Case-insensitive email handling: We store both email (preserving user input) and email_lowercase (for queries) rather than using a functional index with LOWER(). This gives us:

- Better query performance (no computation on every lookup)

- Database-agnostic design (functional indexes vary across databases)

- Simpler query plans that the optimizer can understand

Partial unique index: The constraint WHERE verified_at IS NOT NULL AND deleted_at IS NULL is critical. It allows users to attempt adding an email, have it fail verification, try again, etc. But once verified, that email is locked to one user within the organization.

Soft deletes: The deleted_at timestamp lets us maintain a complete audit trail. We can see who had which emails when, which is valuable for security investigations and debugging.

Repository Layer: Atomic Operations and Idempotency

The repository layer provides a clean interface for email operations while ensuring data consistency. We use Drizzle ORM for type-safe database queries and schema management. Here are the key method signatures:

export const userAlternateEmailsRepository = {

async insert(data: {

userExternalId: string;

organizationId: string;

email: string;

externalEmailId?: string | null;

}): Promise<UserAlternateEmail[]>,

async markEmailAsVerified(

id: string,

externalEmailId: string

): Promise<UserAlternateEmail>,

async delete(id: string): Promise<UserAlternateEmail>,

async findVerifiedEmailByOrganizationId(

email: string,

organizationId: string

): Promise<UserAlternateEmail | undefined>,

};

The full implementation details are provided below.

userAlternateEmailsRepository implementation

export const userAlternateEmailsRepository = {

// Insert with automatic email normalization

async insert(data) {

const emailLowercase = data.email.toLowerCase();

// Insert record with normalized email

return await db.insert({ ...data, emailLowercase });

},

// Atomic verification - only marks if currently unverified

async markEmailAsVerified(id: string, externalEmailId: string) {

// Update only if: id matches AND verifiedAt IS NULL AND deletedAt IS NULL

const result = await db

.update({

verifiedAt: new Date(),

externalEmailId,

})

.where({ id, verifiedAt: null, deletedAt: null });

if (result.length === 0) {

throw new Error("Unable to verify email");

}

return result[0];

},

// Atomic soft delete - only deletes if not already deleted

async delete(id: string) {

// Update only if deletedAt IS NULL

const result = await db

.update({

deletedAt: new Date(),

})

.where({ id, deletedAt: null });

if (result.length === 0) {

throw new Error("Unable to delete email");

}

return result[0];

},

// Find verified emails with case-insensitive lookup

async findVerifiedEmailByOrganizationId(

email: string,

organizationId: string

) {

return await db.findFirst({

where: {

organizationId,

emailLowercase: email.toLowerCase(),

verifiedAt: notNull,

deletedAt: null,

},

});

},

};

The markEmailAsVerified and delete methods are idempotent by design. If you call markEmailAsVerified twice, the second call fails gracefully. Same with delete. This prevents race conditions and makes retry logic safe.

Preventing Duplicate Emails

One of our biggest challenges was ensuring an email can only be verified once within an organization. We needed to check multiple user tables across our system and the alternate emails table itself.

Here’s how we implemented the availability check:

isEmailAvailable implementation

async isEmailAvailable(

userExternalId: string,

email: string,

organizationId: string

): Promise<boolean> {

const emailLowercase = email.toLowerCase();

// Check all user tables in parallel

// Note: This parallel approach is not ideal, but because we store user records

// across multiple tables with different schemas (legacy architecture), it's

// difficult to filter with just one query. We use Promise.all() for better

// performance. While not optimal, it works functionally and we haven't

// observed major performance issues in production.

const [

user1,

user2,

user3,

user4,

verifiedAlternateEmail,

] = await Promise.all([

// Check user table 1

dbClient.query.users1.findFirst({

where: and(

eq(users.email, emailLowercase),

ne(users.userId, userExternalId), // Allow user's own email

),

}),

// Check user table 2

dbClient.query.users2.findFirst({

where: and(

eq(users.email, emailLowercase),

ne(users.userId, userExternalId),

),

}),

// Check user table 3

dbClient.query.users3.findFirst({

where: and(

eq(users.email, emailLowercase),

ne(users.userId, userExternalId),

),

}),

// Check user table 4

dbClient.query.users4.findFirst({

where: and(

eq(users.email, emailLowercase),

ne(users.userId, userExternalId),

),

}),

// Check verified alternate emails in this organization

userAlternateEmailsRepository.findVerifiedEmailByOrganizationId(

email,

organizationId

),

]);

// Email is available if it doesn't exist in any table

return !user1

&& !user2

&& !user3

&& !user4

&& !verifiedAlternateEmail;

}

We call this function twice: once when the user tries to add the email, and again during the verification callback. The second check is crucial—it prevents a race condition where two users try to add the same email simultaneously.

Server Actions: The Business Logic Layer

We implemented three main Next.js Server Actions for email management:

Adding a New Email

This is the first touchpoint when a user wants to add an alternate email. The function performs several validation checks before creating an unverified email record and triggering the verification flow:

- Email format validation - Ensures the email is valid before doing any database work

- Limit check - Users can have a maximum of 5 alternate emails to prevent abuse

- Availability check - Verifies the email isn’t already in use by another account

- Database insert - Creates an unverified record (with

verifiedAt: null) - Send verification - Triggers the magic link email via our authentication service

The key design choice here is creating the unverified record immediately, even before the user verifies. This allows users to see their pending emails in the UI and lets us track verification attempts.

addAlternateEmail Server Action

"use server";

export async function addAlternateEmail(

email: string,

userExternalId: string,

organizationId: string,

verifyRedirectUrl: string

) {

// Validate email format

if (!validateEmail(email)) {

return { success: false, error: "Invalid email format" };

}

// Check limit (max 5 alternate emails)

const existingCount = await getExistingEmailCount(

userExternalId,

organizationId

);

if (existingCount >= 5) {

return { success: false, error: "Maximum of 5 alternate emails allowed" };

}

// Check if email is available (not used by another account)

const isAvailable = await isEmailAvailable(

userExternalId,

email,

organizationId

);

if (!isAvailable) {

return { success: false, error: "Unable to add this email..." };

}

// Insert unverified email record

const alternateEmail = await repository.insert({

userExternalId,

organizationId,

email,

});

// Trigger verification email via auth service

await authClient.sendVerificationEmail({

email,

userId: userExternalId,

organizationId,

verifyRedirectUrl,

});

return { success: true, alternateEmailId: alternateEmail.id };

}

Verifying an Email

The verification flow involves multiple services working together. When a user clicks the magic link in their email:

- Magic link redirects to auth service: The Stytch magic link directs the user to our authentication service

- Stytch validation: The auth service calls Stytch’s API to validate the magic link token is legitimate and hasn’t expired

- Session establishment: After successful validation, the auth service generates an HTTP-only cookie with a signed JWT that identifies the user across all Tint domains

- Signed verification data: The auth service creates a cryptographically signed payload containing the user ID, organization ID, email, and Stytch member ID

- Redirect to Protection Portal: The user is redirected back to the Protection Portal with the signed data

- Final verification: The Protection Portal validates the signature, performs a second availability check to prevent race conditions, then atomically marks the email as verified in the database

verifyEmailCallback Server Action

"use server";

export async function verifyEmailCallback(signedData: string) {

// Validate cryptographic signature

const payload = validateSignedData(signedData);

if (!payload) {

return { success: false, error: "Invalid or expired verification link" };

}

const { userId, organizationId, email, externalEmailId } = payload;

// Find the unverified email record

const unverifiedEmail = await findUnverifiedEmail(

userId,

organizationId,

email

);

if (!unverifiedEmail) {

return { success: false, error: "Email not found or already verified" };

}

// Re-check availability (prevents race conditions)

const isAvailable = await isEmailAvailable(userId, email, organizationId);

if (!isAvailable) {

// Email was claimed by another user during verification

await repository.delete(unverifiedEmail.id);

return { success: false, error: "Unable to verify this email..." };

}

// Mark as verified atomically

await repository.markEmailAsVerified(unverifiedEmail.id, externalEmailId);

return { success: true };

}

Deleting an Email

deleteAlternateEmail Server Action

"use server";

export async function deleteAlternateEmail(

emailId: string,

userExternalId: string,

organizationId: string

) {

// Verify ownership

const email = await repository.getById(emailId);

if (

!email ||

email.userExternalId !== userExternalId ||

email.organizationId !== organizationId

) {

return { success: false, error: "Unable to delete email" };

}

// Soft delete in database (source of truth)

await repository.delete(emailId);

// Best-effort cleanup in Stytch (non-blocking)

if (email.externalEmailId) {

try {

await authClient.deleteEmail(email.externalEmailId, organizationId);

} catch (error) {

console.warn("Stytch cleanup failed, but database delete succeeded");

// Don't throw - deletion already succeeded in our database

// Periodic cleanup job handles orphaned Stytch members

}

}

return { success: true };

}

The key design principle here: our database is the source of truth. If we successfully delete from the database but Stytch cleanup fails, we still return success. We maintain a manual cleanup process to periodically reconcile any orphaned Stytch member records with our database, ensuring data consistency over time.

Stytch Integration: Managing User Mappings

To maintain the relationship between Tint’s user concept (one user, many emails) and Stytch’s member concept (one member, one email), we store a mapping in DynamoDB:

interface StytchUserMapping {

tintUserId: string;

stytchMemberId: string;

createdAt: string;

}

This minimal mapping allows us to:

- Look up which Stytch member corresponds to a Tint user

- Handle multiple emails per user by maintaining multiple mappings

- Track when each mapping was created

Future Enhancement: We could store the alternateEmailId from the user_alternate_emails table in this mapping. This would provide a direct link between the DynamoDB mapping and the Postgres record, making cleanup operations more efficient. However, for our current use case, the minimal mapping works well since we can always query Postgres to find the email associated with a Stytch member ID.

Here’s how we send verification emails:

sendVerificationEmail implementation

export async function sendVerificationEmail({

email,

userId,

organizationId,

verifyRedirectUrl,

}) {

// Map Tint organization to Stytch organization

const stytchOrgId = await getStytchOrganizationId(organizationId);

// Check if Stytch member already exists for this email

let stytchMemberId = await getStytchMemberIdForEmail(email, stytchOrgId);

// Create member if doesn't exist

if (!stytchMemberId) {

const member = await createStytchMember({

organizationId: stytchOrgId,

email,

userId, // Reference for lookup

});

stytchMemberId = member.id;

// Store mapping: Tint User ID <-> Stytch Member ID

await upsertMapping({ tintUserId: userId, stytchMemberId });

}

// Send magic link email

await sendStytchMagicLink({

organizationId: stytchOrgId,

email,

redirectUrl: verifyRedirectUrl,

templateId: VERIFICATION_TEMPLATE_ID,

});

return { success: true };

}

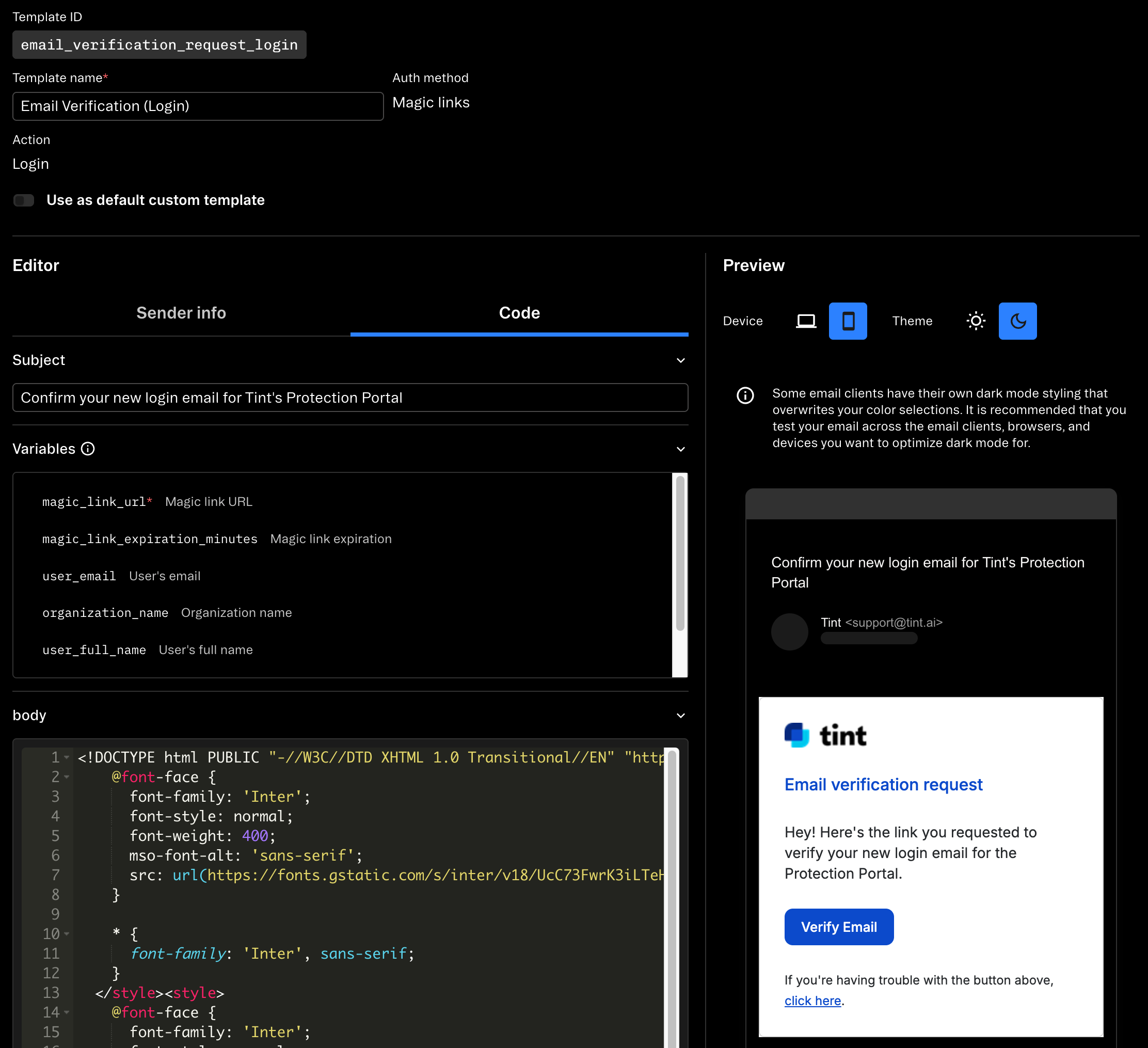

We customize the email verification template in Stytch’s dashboard:

| Field | Value |

|---|---|

| Email Subject | “Confirm your login email for Tint’s Protection Portal” |

| Email Body | “Hey! Here’s the link you requested to verify your login email for the Protection Portal.” |

| CTA Button | “Verify Email” |

This clearly differentiates verification emails from login emails, reducing user confusion.

Migration Strategy: From Hardcoded List to Database

This migration followed our standard change management process with proper testing, approval, and rollback plans.

We couldn’t just flip a switch—we had 71+ existing alternate emails in production that users relied on. We needed a smooth migration path.

Phase 1: Create Database Table and Populate

We created the user_alternate_emails table and wrote a script to migrate the hardcoded list:

// Migration script (run once in production)

const hardcodedEmails = [

{ email: "user1@example.com", userId: "abc123", orgId: "org-1" },

{ email: "user2@example.com", userId: "def456", orgId: "org-2" },

// ... 71+ more

];

for (const { email, userId, orgId } of hardcodedEmails) {

await userAlternateEmailsRepository.insert({

userExternalId: userId,

organizationId: orgId,

email,

// Note: We mark these as verified since they're already in production

verifiedAt: new Date(),

});

}

Phase 2: Dual Lookup (Temporary Compatibility Layer)

We modified the login flow to check both the database and the hardcoded list:

getUserByEmail with dual lookup

async function getUserByEmail(email: string, organizationId: string) {

// First, try alternate emails in database

const alternateEmail =

await userAlternateEmailsRepository.findVerifiedEmailByOrganizationId(

email,

organizationId

);

if (alternateEmail) {

return await usersRepository.getByExternalId(alternateEmail.userExternalId);

}

// Fallback to legacy hardcoded list (temporary)

const legacyEmail = HARDCODED_EMAILS.find(

(e) =>

e.email.toLowerCase() === email.toLowerCase() &&

e.organizationId === organizationId

);

if (legacyEmail) {

return await usersRepository.getByExternalId(legacyEmail.userExternalId);

}

// Finally, try primary email in user tables

return await usersRepository.getByEmail(email);

}

This ensured zero downtime during the migration.

Phase 3: Remove Hardcoded List

After validating that all lookups worked correctly, we removed the hardcoded list from the codebase entirely. This eliminated the PII security risk and simplified our code.

The Results: Orders of Magnitude Improvement

Since launching on October 27, 2025, the results have exceeded our expectations.

User Adoption

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Users with alternate emails | 252 |

| Total emails added | 256 (~1 per user) |

| Verification rate | 95.88% (256 verified of 267 attempted) |

| Average verification time | 15 seconds |

| Slowest verification time | 8 minutes |

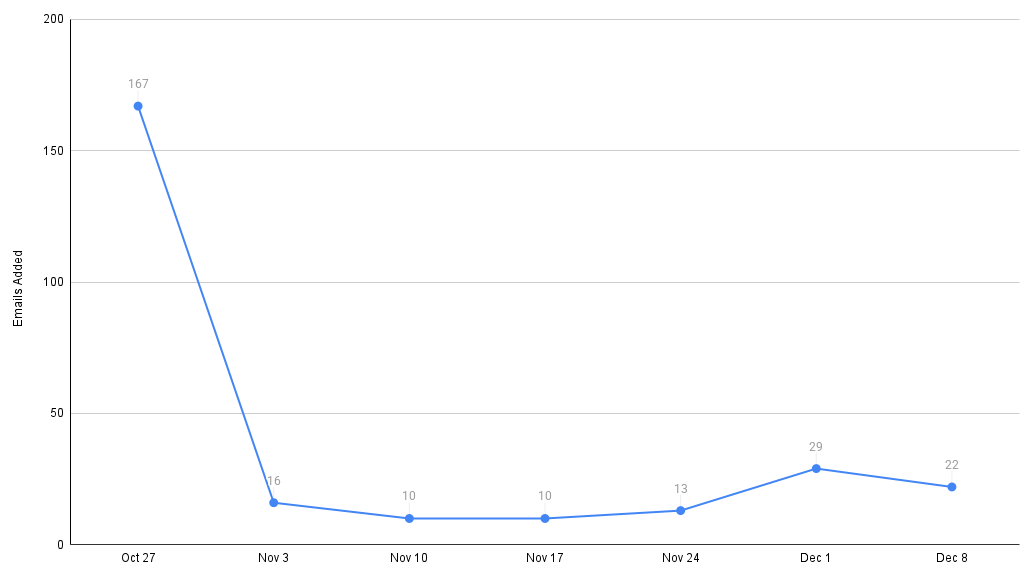

Weekly Email Additions Since Launch

After the initial spike of 167 emails in launch week, the feature settled into steady organic usage of 10-29 emails per week. This consistent baseline suggests the feature addresses an ongoing need. It also hints at how many support tickets we’ve avoided—and will continue to avoid—going forward, relieving our operations and engineering teams of this mundane task.

Operational Impact

- 100% reduction in support tickets: 0 tickets after launch vs 2.46 tickets/month before (33 tickets over 13 months)

- Zero code deployments for email additions (previously 34 PRs)

- 46,000x faster turnaround: 15 seconds vs 7.98 days (191.4 hours)

- Eliminated manual work: Previously required engineer time for each of 71+ emails

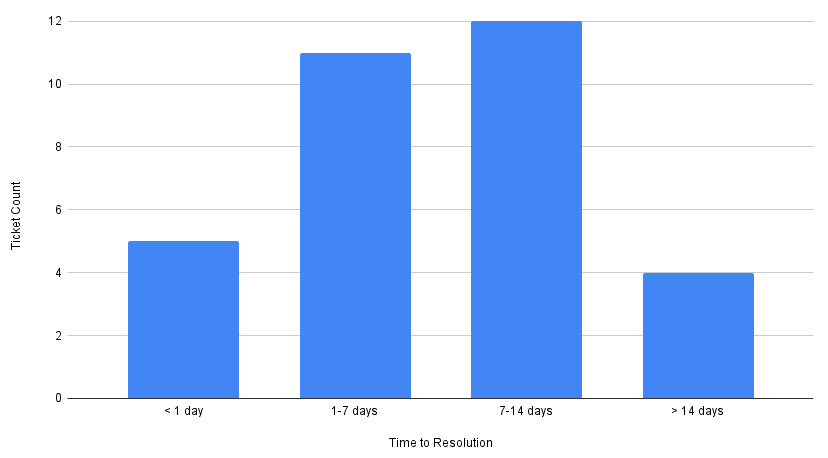

Ticket Resolution Times (Pre-Launch)

Pre-launch, most tickets took 1-2 weeks to complete, which makes sense given the process: create PR, code review, merge, deploy, and verify in production. The wide distribution from 3 hours to 28 days reflects the unpredictability of the manual process—faster turnaround depended on engineer availability and deployment schedules. This inconsistency made it difficult to set user expectations.

Email Verification Success

| Status | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Verified | 256 | 95.88% |

| Pending verification | 7 | 2.62% |

| Deleted | 4 | 1.50% |

Post-launch, the 95.88% verification rate is excellent. Even in the worst case, a user verified their email in 8 minutes—still dramatically faster than the 7-8 day average from the manual process! The 7 pending emails are likely users who started the process but haven’t checked their email yet. The 4 deleted emails represent users who changed their mind or added the wrong email.

System Performance

We monitor performance metrics in Datadog to ensure the system scales:

- Average add email API response time: ~200ms

- Average verification callback time: ~150ms

- Stytch API call success rate: 98.3% (59 total errors, mostly expired magic links)

The errors we’ve seen from Stytch are almost entirely user-initiated: clicking an expired magic link, or clicking the same link twice. These are handled gracefully with clear error messages.

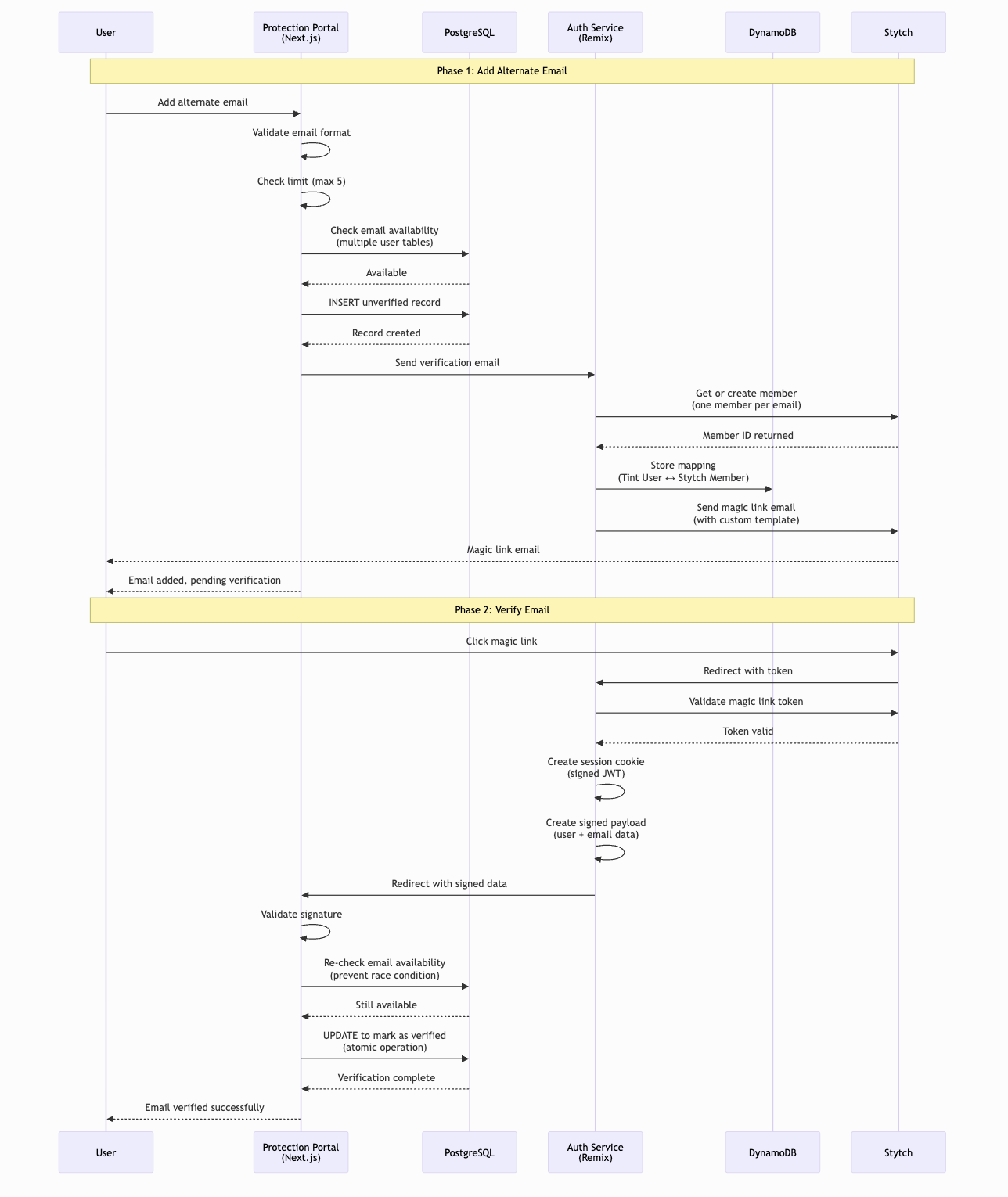

Putting It All Together: The Complete Verification Flow

Now that we’ve covered the individual components, let’s see how everything works together when a user adds a new alternate email. This sequence diagram below shows the complete flow from initial request to successful verification.

Add Alternate Email Sequence Diagram

This flow demonstrates several key security and reliability patterns:

- Email availability check happens early to fail fast if the email is already in use

- Unverified record created immediately so the user can see it’s pending

- Stytch member creation is decoupled from the initial request (async process)

- DynamoDB mapping created to link Tint and Stytch concepts

- Cryptographic signature ensures integrity when redirecting back to Protection Portal

- Final availability check before verification prevents race conditions

- Atomic database update marks email as verified and stores external ID

The diagram also shows our graceful error handling: if the email is unavailable or the user has reached the limit, we provide clear feedback immediately without making unnecessary external service calls.

Key Architectural Lessons

1. Database as Source of Truth

We designed the system so that our database operations always succeed, even if external services (Stytch, auth service) fail. When deleting an email, we:

- Delete from our database (source of truth)

- Then attempt to clean up Stytch (best-effort)

If step 2 fails, we log a warning but still return success to the user. We maintain a manual cleanup process to periodically reconcile orphaned Stytch members with our database records. This cleanup job is documented, access-controlled, and runs on a regular schedule as part of our operational procedures.

2. Idempotent Operations Are Your Friend

Both markEmailAsVerified and delete are idempotent. This makes retry logic simple and prevents race conditions. If a user clicks “verify” twice, the second call fails gracefully. If a network issue causes a retry, the operation safely no-ops.

3. Soft Deletes for Audit Trails

We initially considered hard deletes, but soft deletes via deleted_at provide valuable benefits:

- Complete audit trail for security investigations

- Ability to recover from accidental deletions

- Historical analysis of user behavior

- Compliance with data retention policies

The cost is minimal: a slightly more complex query with WHERE deleted_at IS NULL.

4. Case-Insensitive Email Handling

Storing email_lowercase alongside email was the right choice. We considered:

- Functional index with LOWER(): Requires computation on every query

- CITEXT column type: Requires computation on every query, PostgreSQL-specific

- Two columns: Simple, fast, database-agnostic

The two-column approach with a CHECK constraint ensures consistency without the downsides of the alternatives.

5. Partial Unique Index for Multi-Step Verification

The constraint WHERE verified_at IS NOT NULL AND deleted_at IS NULL is subtle but critical. It allows:

- Multiple unverified attempts (user can retry if verification fails)

- Only one verified email per org (prevents account hijacking)

- Soft-deleted emails don’t block new additions

Without this partial index, we’d need application-level locking or more complex validation logic.

6. Multi-Tenant Design from Day One

Every operation is scoped to organizationId. This prevents cross-org data leakage and makes it easy to support multiple organizations. When we add new organizations, the system automatically works with zero code changes.

7. Progressive Enhancement and Backwards Compatibility

The dual-lookup system during migration was crucial. We couldn’t have a “flip the switch” cutover—that would risk breaking existing users. By checking both the database and the hardcoded list, we had zero downtime and could roll back if needed.

8. Cryptographic Signatures for Secure Callbacks

Using cryptographically signed tokens for verification callbacks prevents tampering and ensures only legitimate verification requests are processed. This is critical for preventing account hijacking attempts.

9. Working Within API Constraints

The Stytch B2C/B2B limitation forced us to rethink our approach. Instead of fighting the constraint, we embraced it: one Stytch member per email. Sometimes the best solution isn’t the one you planned—it’s the one that works with the tools you have.

10. Generic Error Messages to Prevent Email Enumeration

We use generic error messages when an email is unavailable or verification fails. Instead of specific messages like “This email is already associated with another account,” we return “Unable to add this email. Please try a different email or contact support.”

This prevents email enumeration attacks, where an attacker could probe the system to discover which emails have accounts. By providing the same generic message regardless of whether the email exists, we protect user privacy and make reconnaissance harder.

Additional protections we implement:

- Rate limiting: Users can only attempt to add 5 emails before hitting their limit

- Organization scoping: All operations are limited to the user’s organization, preventing cross-org enumeration

- Monitoring: We track failed addition attempts to detect suspicious patterns

What We’d Do Differently

Consolidate User Tables

The parallel query approach for checking email availability is functional but not ideal. Our legacy architecture stores user records across multiple tables with different schemas, requiring us to query each table separately.

If we were starting fresh, we’d design a single user table in Postgres to store all user records regardless of type. This would:

- Eliminate the need for parallel queries

- Simplify the

isEmailAvailablecheck to a single database query - Improve maintainability and reduce complexity

- Make it easier to add new user types in the future

Use Postgres for All Mappings

We currently store the Stytch-to-Tint user mappings in DynamoDB, which introduces a second data store into the architecture. While DynamoDB provides good performance, having all data in Postgres would:

- Reduce infrastructure complexity (one data store instead of two)

- Simplify backup and disaster recovery

- Allow for JOIN queries between user records and Stytch mappings

- Eliminate the need to synchronize data across two systems

This would make the system easier to reason about and maintain in the long term.

Better Metrics from Launch

We added detailed logging and metrics after launch when we wanted to write this blog post. We should have instrumented from the beginning:

- Verification funnel (emails added → verification sent → clicked → verified)

- Time-to-verify percentiles (p50, p95, p99)

- Error rates by error type

Having these metrics from day one would have given us earlier insight into user behavior.

A Note on Security

We’ve generalized some implementation details in this post for security reasons. Things like exact error messages, some table names, and specific secret management approaches aren’t fully detailed here. All cryptographic keys and secrets are managed using industry-standard secret management tools, logs are sanitized to avoid storing PII or tokens, and our manual processes are access-controlled and regularly reviewed as part of our SOC 2 compliance program.

Conclusion: Self-Service at Scale

Building a self-service email management system taught us that great developer experiences come from thoughtful architecture. By choosing PostgreSQL over Redis, soft deletes over hard deletes, and atomic operations over optimistic locking, we built a system that’s both fast and reliable.

The results speak for themselves: we’ve eliminated 100% of support tickets, reduced turnaround time by ~46,000x, and enabled 252 users to manage their own login credentials. More importantly, we’ve removed PII from our codebase and given users the autonomy they deserve.

If you’re considering building a similar system, the key principles are:

- Database as source of truth - external services are best-effort

- Idempotent operations - make retry logic safe and simple

- Soft deletes - audit trails are worth the query complexity

- Partial unique indexes - constrain only what needs constraining

- Multi-tenant from day one - don’t bolt it on later

- Progressive migration - backwards compatibility during cutover

- Cryptographic signatures - secure inter-service communication

- Work within API constraints - adapt your design to external service limitations