pytest stands as the de facto standard for automated testing in Python. Its simplicity, its fixture system, and extensive plugins make it the go-to solution for maintainable test suites. Naturally, we chose pytest to write tests for one of our new projects. However, we encountered some challenges related to the use of dots in filepaths.

The Challenge with Dot-Containing Filepaths

Our project leverages Windmill, a modern task orchestrator recommended by our friends at Qovery. However, Windmill exports scripts using filepaths that contain dots, such as import.flow/import_data.inline_script.py.

When we attempted to test this module with the following import:

from import_data.inline_script import import_users

It resulted in the error below:

___ ERROR collecting f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script_test.py ___

ImportError while importing test module '/app/f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script_test.py'.

Hint: make sure your test modules/packages have valid Python names.

Traceback:

/usr/local/lib/python3.13/importlib/__init__.py:88: in import_module

return _bootstrap._gcd_import(name[level:], package, level)

E ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'import_data'

The error occurs because the Python interpreter treats dots as delimiters in module names, which are used to separate packages and submodules. In this case, Python misinterprets the intended structure by assuming that inline_script is a submodule of the import_data package, instead of recognizing import_data.inline_script as a single module. Hence the failure.

We confirmed this behavior with the Windmill team. They mentioned that their internal logic uses the .inline_script naming convention, and they currently have no option for customization. Although this is most likely a temporary issue, we had to devise a workaround, as only fully-tested code could make it to production.

Abandoned Solutions

During our exploration, we evaluated three potential approaches. Let’s start by reviewing the first two solutions that we ultimately abandoned.

- Renaming the files by modifying the names directly within

pytest, via theconfigurehooks. - Running a pre-test script to rename the files before launching the

pytestcommand.

We won’t delve into the implementation details of these two experiments, but we’ll explain why we decided to ignore them in favor of the third approach.

If you are only interested by the working solution, you can jump to the solution.

Renaming the Files within Pytest

One approach we considered was renaming the files directly within pytest, using the pytest_configure and pytest_unconfigure functions. They run before and after the test execution, respectively.

from pathlib import Path

# Windmill generates files with names like "foo.inline_script.py", but Python does not accept the extra dot in filenames.

# Therefore, we replace ".inline_script" with "-inline_script" to avoid import issues.

def pytest_configure(config):

"""

Rename files ending in `.inline_script_test.py` to `-inline_script_test.py` before test collection.

"""

base_dir = Path(__file__).parent

renamed_files = []

for file in base_dir.rglob("*.inline_script_test.py"):

new_name = file.with_name(file.name.replace(".inline_script_test.py", "-inline_script_test.py"))

file.rename(new_name)

renamed_files.append((new_name, file))

config._renamed_test_files = renamed_files

def pytest_unconfigure(config):

"""

Restore renamed test files after tests have run.

"""

renamed_files = getattr(config, "_renamed_test_files", [])

for new_file, original_file in renamed_files:

if new_file.exists():

new_file.rename(original_file)

This solution worked well with pytest. However, to further enhance our developer experience, we wanted to use a watch mode leveraging pytest-watch. Unfortunately, pytest-watch does not account for these hooks, making this solution unsuitable for our workflow.

Using a Pre-Test Script to Rename Files

Another approach we considered was creating a Bash script to rename all the files before launching the Python tests - whether with pytest or pytest-watch. Since we use a Makefile to start our tests, incorporating pre- and post-renaming steps was straightforward. For example, our Makefile includes targets like:

test-pre-renaming-hook:

./bin/preTestRenamingHook.sh

test-post-renaming-hook:

./bin/postTestRenamingHook.sh

test: test-pre-renaming-hook

$(DOCKER_COMPOSE_TEST) pytest pytest || $(MAKE) test-post-renaming-hook

$(MAKE) test-post-renaming-hook

test-watch: test-pre-renaming-hook

$(DOCKER_COMPOSE_TEST) pytest pytest-watch || $(MAKE) test-post-renaming-hook

$(MAKE) test-post-renaming-hook

This solution introduces a significant drawback: it makes import statements less intuitive for our Engineers. The post-test phase must rename the files back to their original names, which may also contain underscores. Therefore, we can’t simply convert every dot into an underscore; we need a dedicated character sequence that can be reliably reverted. We chose to use the __DOT__ sequence.

The renaming is fully abstracted within the Makefile, making it invisible to the Engineer. As a result, when an Engineer wants to import their module, they would naturally write:

from import_data.inline_script import import_users

Which won’t work, as the module is now import_data__DOT__inline_script. They should instead write:

from import_data__DOT__inline_script import import_users

This solution is not intuitive and introduces unnecessary friction for our Engineers, which goes against our Platform team’s mission to make development as seamless as possible.

One might argue that we could dynamically modify the test files during runtime to update the import statements. However, this approach would significantly increase complexity and introduce potential race conditions that we are keen to avoid. Ultimately, although the solution might work in theory, its complexity and maintenance cost were too high to justify its implementation.

Solution: Importing a Python Module by Filepath (Even With Dots)

Our end-goal is to enable importing a module by its path, like:

module = import_from_file('f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script.py')

def test_import_data_should_return_true():

result = module.import_data("file_000.csv")

assert result is True

Let’s implement this function.

Import a Module from its Filepath

For now, let’s define this function directly in our test file. We’ll extract it at a higher-level later.

def import_from_file(filepath: str):

module_name = filepath.replace("/", "_").replace(".", "_")

spec = spec_from_file_location(module_name, filepath)

module = module_from_spec(spec)

spec.loader.exec_module(module)

return module

We first define a module name for the file we are going to import. It should be unique, and hence, we rely on the filename, replacing all special characters by an _. This way, the compiler won’t be confused anymore, as neither slashes nor dots are in the module name. For instance, f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script.py would be attached to the module f_import_flow_flow_import_data_inline_script_py.

We then need to load the module code into the module variable. This is done through a three-step process:

- Generate the module specs (name, source file, cache information, etc.), via the

spec_from_file_location, - Create an empty shell for the module based on its spec thanks to the

module_from_specfunction, - Actually run the module code and populate the empty shell, via the

spec.loader.exec_modulefunction.

Loading a module is not the most straightforward task, but these three lines provide a ready-to-use module object that we can use into our tests.

Disabling Pytest Auto-Collection

However, running pytest will still return the following error:

=== ERRORS ====

___ ERROR collecting f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script_test.py ____

ImportError while importing test module '/app/f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script_test.py'.

Hint: make sure your test modules/packages have valid Python names.

Traceback:

/usr/local/lib/python3.13/importlib/__init__.py:88: in import_module

return _bootstrap._gcd_import(name[level:], package, level)

E ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'fetch_files_and_validate_them'

=== short test summary info ===

ERROR f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script_test.py

!!! Interrupted: 1 error during collection !!!!

====== 1 error in 0.14s =======

The penultimate line is the most important one: there is an error during the tests collection phase. During this phase, pytest scans the filesystem for test modules and tries to import them using the standard Python naming conventions. Hence, it chokes even before executing our custom import file, as one of our filenames contains a dot.

We didn’t find a way to disable the collection phase. Instead, we are going to replace it with a custom collection, through a tests/pytest/run_dotted_test.py script:

import sys

import types

import traceback

from importlib.util import spec_from_file_location, module_from_spec

## Some helpers to have a fancier output

class Colors:

GREEN = "\033[92m"

RED = "\033[91m"

YELLOW = "\033[93m"

RESET = "\033[0m"

## The function we created in the previous section

def import_from_file(filepath: str):

module_name = filepath.replace("/", "_").replace(".", "_")

spec = spec_from_file_location(module_name, filepath)

module = module_from_spec(spec)

spec.loader.exec_module(module)

return module

## Run the tests available in a given file

def run_tests(filepath: str, module: types.ModuleType) -> int:

failures = 0

## Custom collection phase: get all the `test_` functions defined in the module

test_funcs = [

(name, getattr(module, name))

for name in dir(module)

if name.startswith("test_") and callable(getattr(module, name))

]

if not test_funcs:

print(f"{filepath} :: no test functions found")

return 0

print(f"\nCollected {len(test_funcs)} tests from {filepath}\n")

## Run all the test functions and display the test status

for name, fn in test_funcs:

label = f"{filepath}::{name}"

try:

fn()

print(f"{label} {Colors.GREEN}PASSED{Colors.RESET}")

except AssertionError:

print(f"{label} {Colors.RED}FAILED{Colors.RESET}")

traceback.print_exc()

failures += 1

except Exception:

print(f"{label} {Colors.RED}ERROR{Colors.RESET}")

traceback.print_exc()

failures += 1

## If no failure, the test passed. Otherwise, it will fail the process.

return failures

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("Usage: python run_dotted_test.py path/to/test_file.py")

sys.exit(1)

filepath = sys.argv[1]

try:

mod = import_from_file(filepath)

result = run_tests(filepath, mod)

sys.exit(result)

except Exception:

print(f"{Colors.RED}Unexpected error while loading or running {filepath}{Colors.RESET}")

traceback.print_exc()

sys.exit(1)

This code is quite verbose, due to the output formatting. But it boils down to two steps:

- Import the module from the filepath,

- Collect and run all the functions starting with

test_in this file.

All the rest of the code is some refined ChatGPT magic to mimic the pytest output.

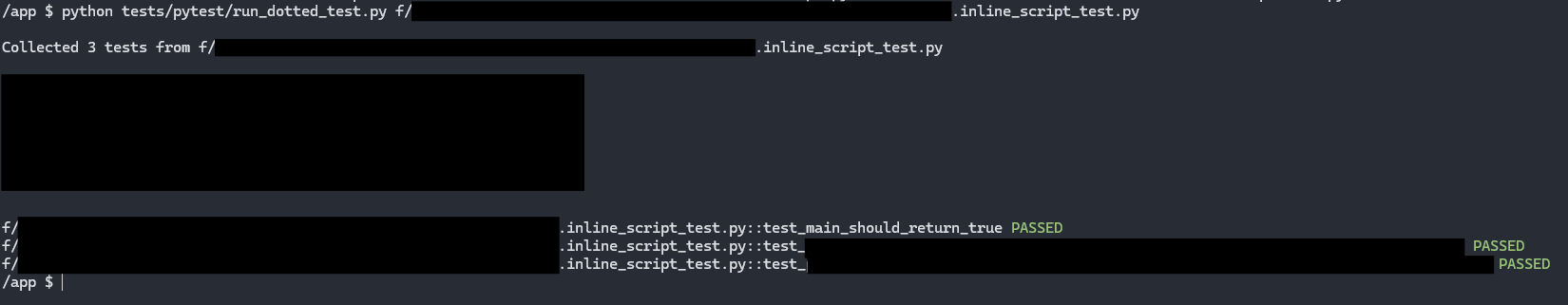

We can now run our test using the command:

python run_dotted_test.py f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script_test.py

Which produces an output similar to:

Note that we re-created the same function import_from_file as the one we have defined in our test file. To keep our code DRY, we can use our run_dotted_tests module instead:

from run_dotted_test import import_from_file

module = import_from_file('f/import_flow.flow/import_data.inline_script.py')

def test_import_data_should_return_true():

result = module.import_data("file_000.csv")

assert result is True

Running All your Project Tests

The previous script runs tests from a single file. To execute tests across all the *_test.py files in our project, we can write some shell:

#!/bin/sh

exit_code=0

for file in $(find f -name '*_test.py'); do

python tests/pytest/run_dotted_test.py "$file"

result=$?

if [ "$result" -ne 0 ]; then

exit_code=$result

fi

done

exit $exit_code

This script locates all files ending with _test.py and runs them using our custom runner (run_dotted_test.py). It also captures any non-zero exit codes, ensuring that if any test fails, the overall exit code reflects the error, triggering a failure in our CI system.

We can now run all our tests, even with dot-containing filepaths, by running this script.

Watch Mode

To improve the developer experience, we need a watch mode. When running in watch mode, we want to run all the tests from the test file currently edited (eg. foo_test.py). We also want to run all the tests when editing the code file associated with this test file (eg. foo.py).

Due to similar issues as the pytest collection phase, we can’t use the pytest-watch package. Instead, we are going to leverage the watchexec package.

watchexec --exts py \

--restart \

--emit-events-to=json-stdio \

./watch_dotted_test.sh

We are listening to changes from all Python files, and are going to emit the changed file data into JSON format (that we can easily manipulate using jq). When a file is changed, we’ll call a new watch_dotted_test.sh script:

#!/bin/sh

read event_json

# Retrieve the path of the file that trigger this change event

changed_file=$(echo "$event_json" | jq -r '.tags[] | select(.kind == "path") | .absolute')

if [ ! -f "$changed_file" ]; then

exit 0

fi

# If editing the code file, try to run the associated test file

if echo "$changed_file" | grep -q '_test\.py$'; then

test_file="$changed_file"

else

test_file="${changed_file%.py}_test.py"

fi

# Run the test file if it ever exists

if [ -f "$test_file" ]; then

exec python run_dotted_test.py "$test_file"

fi

We now have a functional watch mode, speeding up our Engineering work. When a file is changed, we can have an immediate feedback about our changes.

And that’s finally the end of this long journey. That’s definitely a lot of work for a single extra . into our filepaths. Fortunately, this is a one-time setup that we can just forget!